#THEMTOO: the case of Hedy Lamarr, bombshell scientist, in the age of the #metoo movement

For a woman, surely, there can’t be many life experiences as dreadful as rape. Even so- called “consensual” sex can be hard to bear when, for work-related or other reasons a woman has to give in to a man in whom she has no interest, in the best of cases, or by whom she is repulsed, in the worse. Think creepy, porcine Weinstein.

But rape, sexual harassment, abuse, pay inequality, when pay there is–and you can no doubt add to the list–are just some of the indignities or the appalling situations women go through. We have come a long way, I know, we truly have. In most developed countries, mainly in the last century and the present one, the revolting unfairness of many women’s lives has slowly and gradually given way to more awareness, driven the more egregious and untenable sins against women of men and the society on the whole into oblivion or, at the very least, underground.

Despite the recent #metoo brouhaha, we have to keep our fingers crossed that not everything will be shortly forgiven and forgotten, as it too often is. Much remains to be redressed and no oversight or failure is corrected forever. Still we should consider ourselves lucky when we compare our fate to those of women living under less progressive rules.

Even in the new era of openness and direct accusations and of the worse transgressors being brought to justice, the unfairness with which women were and are treated is daily and forcibly brought home. Looking back, it’s worse.

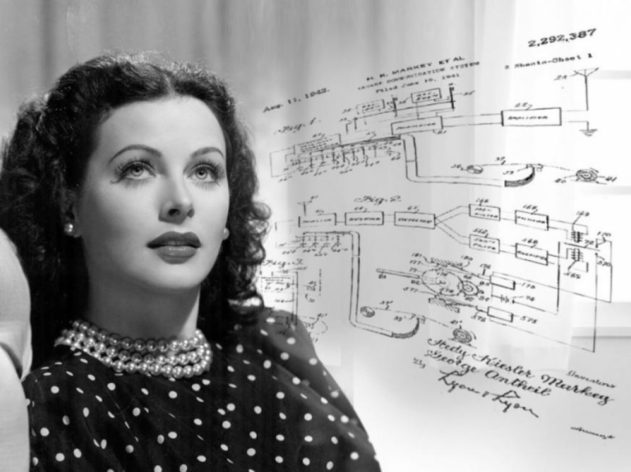

Take the case of Austrian-born Hedy Lamarr, whose story Alexandra Dean tells in the documentary “Bombshell, the Hedy Lamarr story,”* screened at the last Tribeca Festival. Lamarr had no illusion about what a woman, no matter how stunning, needs to do to get somewhere. In Hollywood where she was known in the forties as the most glamorous star, bar none, she quipped, “The ladder of success in Hollywood is usually agent, director, producer, leading man. And you are a star if you sleep with them in that order. Crude but true.” But even if she did abide by that rule, which she may well have, mistakes in her career choices and a complicated private life never allowed her to reach the elevated heights where reigned the Rita Hayworths and Lauren Bacalls of the day, never made her a star whose light would continue to burn bright in cinema history, as do the extinguished actual stars that still glitter in our summer skies.

There is worse. This glamorous woman who, for a number of years, was called the most beautiful one in the world, also had the brilliant, inquisitive mind of an scientific inventor of the first order. For one of her boyfriends, Howard Hughes, she came up with an effective design to streamline the wings on his planes. But mainly, during World War II, she developed a coded radio communication that would guide Allied torpedoes. She called it “frequency hopping,” a technology now universally used in wireless communication, from G.P.S to Bluetooth and Wi-Fi which she and her co-inventor George Antheil patented.

Still, she was a woman and, as such, expected to be beautiful and nothing more, certainly not recognized as someone endowed with a top-notch scientific mind. The frustration must have been immense. At least, she was courted and admired for her stunning physique, unlike other remarkable women such as Rosalind Franklin who, in the sixties, discovered the double-helix molecule in the DNA structure and was made to stay in the shadows while her male colleagues stole her work and ended up with the 1962 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. Or, in earlier times, Nannerl Mozart, a brilliant musician made to set aside any ambition she might harbor of a career in European courts so as to cast no shadow over her brother Wolfgang Amadeus.

So yes, forced sex is an abomination too many women are made to submit to but then, the very fact that women can achieve so many extraordinary things, even in the simple tasks of daily life, is a miracle worthy of great praise. As women engaged in the task of living (in the best cases at least twice as difficult as it is for men) we could spare a thought for Hedy Lamarr who, despite great beauty and what was called, even in her time, scientific genius, was, still, only a woman.

*Outside the US you will need a VPN to view the film.

news via inbox

Nulla turp dis cursus. Integer liberos euismod pretium faucibua