“The spirit of Woodstock lives on.” Interview with BARAK GOODMAN of “Woodstock”

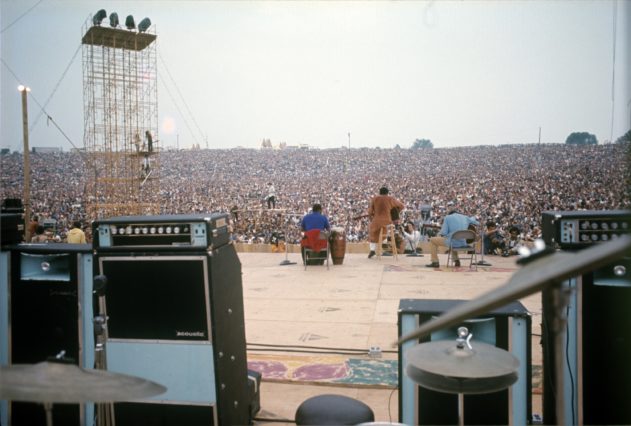

The concert film “Woodstock,” made in 1970 by director Michael Wadleigh, captured the August 1969 “three days of peace and love” music festival in Bethel, New York, the touchstone for a generation and the height of the anti-Vietnam War movement. Joe Cocker, Joan Baez, The Who, Santana and Jimi Hendrix were among the notables who took to that muddy, rainy stage, which Wadleigh’s cameramen and editors, including a young Martin Scorsese, weaved together into a three-hour cinematic opus.

But as the fiftieth anniversary of Woodstock approached, filmmaker Barak Goodman (“Oklahoma City,” “Clinton”) decided it was time to turn the cameras around unto the nearly 400,000 hippies and other young people without whom the event would likely have been quickly forgotten.

“[Of] the big questions about what made Woodstock Woodstock, the answer wasn’t up on stage. It wasn’t the concert, it wasn’t the music,” said Goodman, who co-directed “Woodstock: Three Days That Defined a Generation” with Jamila Ephron. “We felt there was a huge opportunity, a big hole left by the original documentary [regarding] why did this event become the iconic event that it is today.”

Goodman said that Wadleigh’s film “left room for exploration” of who were the people out there in those muddy fields of upstate New York. Goodman and his producers were able to comb through hours and hours of outtakes from “Woodstock” to get crowd shots as a starting point, but he needed testimonials from attendees as well.

Archivist Joel Makower allowed the filmmakers access to his oral history archive of Woodstock attendees recounting the experience, and Goodman’s team also conducted new interviews. However, very quickly he realized he was going for something other than the traditional documentary technique of cutting away from archive footage to present-day talking heads.

“Breaking away to see the faces of septuagenarian ex-hippies would be distracting…and really throw you out of the narrative we wanted to tell you,” said Goodman. “It became clear that we had an opportunity here to create a totally immersive experience.”

Ergo, the voices of the attendees are heard speaking over the edited footage but their faces are never seen, only identified with subtitles. This fosters the immersion that Goodman was seeking to achieve, putting the audience at the point of witnessing, almost in real time, the festival as it appeared to those who were there back in 1969. “It started to become less and less important that we knew who was talking and more important that we never leave that cocoon of the festival,” he said. “Really we wanted the one voice of the audience and the shared experience.”

Goodman’s film also features testimony from festival organizers and townsfolk from the sleepy community of Bethel recounting the friendly hippie invasion (many of the speakers have died since.) One extraordinary moment shows Max Yasgur, the white-haired owner of the farm upon which the festival was staged, speaking amiably from the stage, as much a part of the experience as anyone.

Near the end of the film, Goodman inserts a drone shot of the fields of Yasgur’s farm, long since abandoned by the concert crowd but thankfully preserved for future generations.

“The site of the original festival was purchased by a guy who donated it to this thing called the Bethel Woods Performing Center. It’s [also] a museum, which is wonderful,” Goodman said. “They have performances there all the time, which draw people from all over New York and elsewhere.

“The spirit of Woodstock lives on in this place, and the people who run this facility are ‘Woodstock Nation’ kinds of people. It’s a fun place to visit and feels like you’re back in time, in a way.”

Goodman believes that the word “Woodstock” itself still resonates a half-century on, not only because of the incredible lineup of musical talent that performed there over three days, but, also, due to the fact that teenagers and young adults in their early twenties put together the festival without a precedent, major corporate sponsorship or much help from the “square culture,” as it was known. Add to this the inclement weather and the danger of it “slipping into chaos and something very dark,” and it’s a miracle the festival ever came off at all, let alone not devolve into the kind of nightmare that the ill-fated Woodstock ’99 turned out to be.

“The fact that 450,000 collectively rose to the occasion with the help of townsfolk around them and Max Yasgur […] pulled together and managed to pull through really captured something about that era and generation,” Goodman said of the DIY ethos of Woodstock. “People are drawn to this event as this manifestation or demonstration of what people are capable of as human beings but all too often fail at. I think it’s something we all long for in our world and don’t get enough of.”

Additionally, the sixties generation opposed to the war in Vietnam also found a way to voice their frustrations and share in the common counterculture of music, peace and love and, yes, certainly a substance or two, collectively.

But that spirit of activism hasn’t died. Goodman sees a fierceness to social change evident in his own eighteen- and twenty-one year-old children, in response to the damage left behind by Goodman’s own generation, he believes.

“Global warming is this generation’s Vietnam. I don’t think we’ll see another Woodstock, but I do think we’ll see the kind of political activism like we saw in the sixties, at least some version of it,” he said.

Goodman, who spent two years researching and creating the film from his various sources, will screen “Woodstock: Three Days That Defined a Generation” at the Bethel site this summer in addition to its rolling out in several cities this weekend before airing on “American Experience” later this summer.

“I think [Woodstock] came to represent something about that generation—not the political side but the cultural side of that generation,” the filmmaker said. “There had been a lot of slogans bandied about: peace and love and togetherness and community. But those things became quite real at the festival, because they had to.

“It was the most unlikely among us that demonstrated that it was possible—these seventeen- to twenty-three year-old kids in the mud and the muck. Hungry and tired. They are the ones who showed us the way, and I think there’s something about that.”

“Woodstock: Three Days That Defined a Generation” opens in select theaters this weekend.

news via inbox

Nulla turp dis cursus. Integer liberos euismod pretium faucibua