“The ones that get made are the ones that drop down into your heart and say ‘yes’” (TALKING WITH KEN BURNS AND LYNN NOVICK OF “HEMINGWAY”)

Ken Burns knows he only has so much time left to make a certain number of movies. It’s getting harder to pick and choose which of the many ideas for his trademark multipart documentaries will get his full attention—but choose he must.

“As I get older, I get greedier. Because you realize there are so many subjects that you want to touch, and there’s not gonna be enough time to do them all,” Burns, 67, said this week from his home and offices in Walpole, New Hampshire. “The ones that get made are the ones that drop down into your heart and say ‘yes.’”

I asked him if that notion of limited time is perhaps what finally pushed him to get his latest project with co-director Lynn Novick, “Hemingway,” across the finish line. Death and its inevitability was a major throughline in Ernest Hemingway’s work, and in his life: His father committed suicide when Hemingway was still a young man, and the author took his own life in 1961—like his father, with a shotgun, and almost certainly during a similar bout of severe depression.

“I think what you begin to see in the magnificence of his literature is this very visceral sense of our own mortality. Certainly his [own sense], in a personal way, is [front and center] all the time,” Burns told me, adding that it was natural Hemingway was obsessed with death given his family history of mental illness, his alcoholism, several concussions over many years and being wounded while working in the ambulance corps during the First World War.

“The themes that he [explored] in his work all are delivering us [to] these existential moments,” Burns said. “Think of the title of the short story ‘The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber.’ He’s talking about the nanosecond before his wife blows his brains out. That’s how ‘happy’ his life is.

“But it doesn’t matter, right? Liberation is liberation is liberation.”

“Hemingway,” the three-part, six-hour documentary, is now airing on PBS and on demand. Burns and Novick, who also collaborated on 2017’s “The Vietnam War,” first started tossing around the notion of a doc about the author in the ‘80s. When Novick visited Hemingway’s Ken West home in the nineties, she, Burns and screenwriter Geoffrey C. Ward initially thought the series should begin with a gunshot, indicative of Hemginway’s final moments in Ketchum, Idaho, in 1961.

However, the team eventually scrapped that rather melodramatic beginning.

“You find out at the very, very end of Episode 1 about his” father’s suicide, Burns said, adding that Hemingway’s own suicide is mentioned only in the final moments of Episode 3.

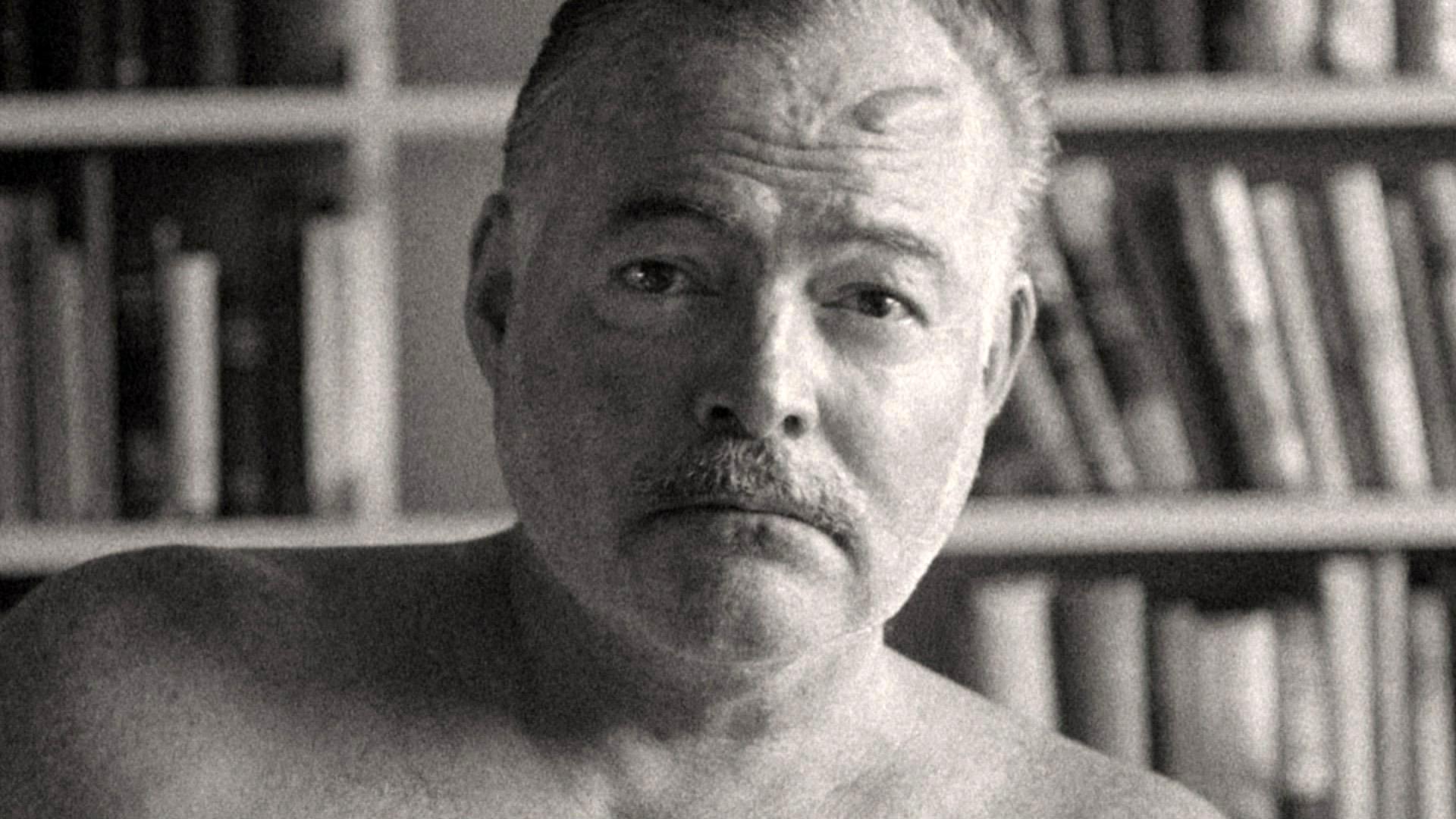

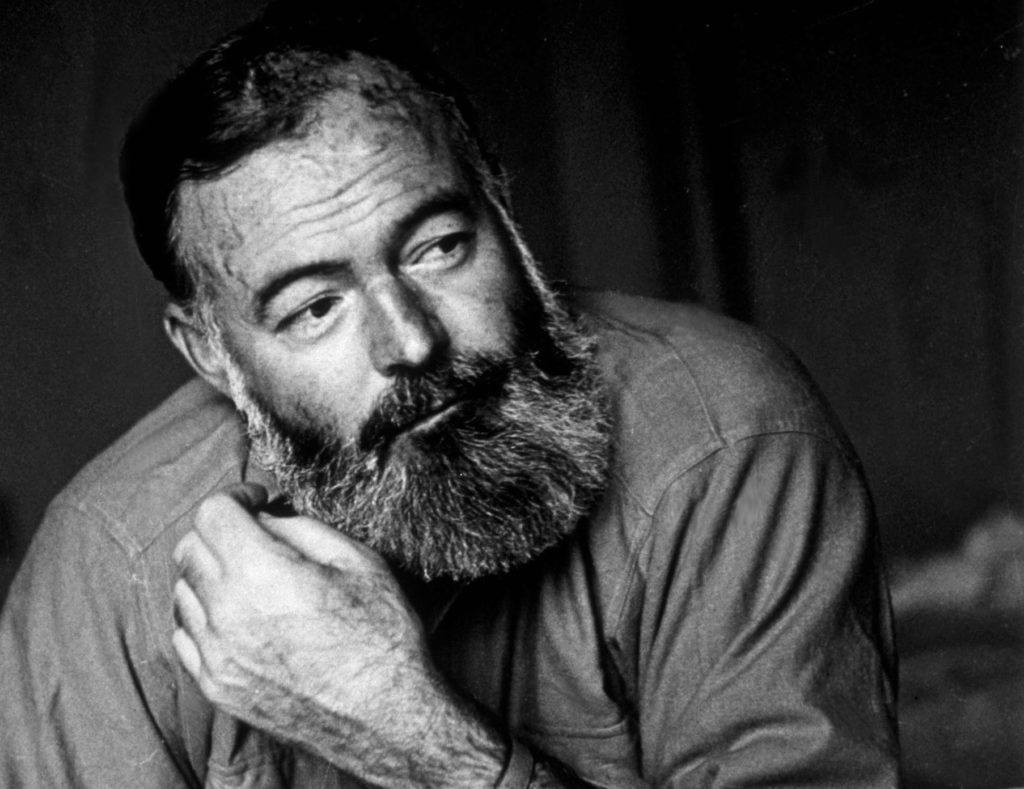

Yes, the author could never get death off of his mind, but his 61 years of life on this earth were also the stuff of legend. After his time in the First World War, which he fictionalized in “A Farewell to Arms,” Hemingway went on to become America’s most renowned man of letters. He reported from Spain during its civil war and raised hell with a circle of intimates in Paris during the 1920s. He drank far too much and could be abusive when drunk—or sober. He married four times, but seemed preternaturally allergic to monogamy. And as the film reports, as a child, his mother enjoyed swapping young Ernest’s clothes for that of his sister—and Hemingway later nudges his wives and lovers to dress more man-like.

All of this informed his singular, spare prose—and his life choices.

“I said to someone along the way, I think it’s our most ‘adult’ film,” Burns said. “I don’t mean it with regard to X-rated [material], though there is a great deal about gender fluidity and sexuality and intimate relations between men and women. I meant the degree of complication, the undertones, the contradictions: Here’s this macho guy that is referred to as a kind of poster boy for toxic masculinity yet has a kind of vulnerability and empathy that allows him to get under the skin of women characters sometimes.”

“Hemingway” co-director Novick said she went back and revisited several of their subject’s books—fiction and reportage—and short stories in preparation for the film, including “A Farewell to Arms” and “The Sun Also Rises.”

“It was such a privilege to reread Heimingway while we were making the film, especially in the context of having spoken with some of these wonderful writers who helped us appreciate him and understand what was enduring about his work,” Novick, who lives in New York, told me this week.

Hemingway’s home in Havana, Cuba, Finca Vigía, is closed to the public, and the house in Ketchum where he ended his life is privately owned. However, Burns and Novick got permission to film in both locations, with Novick making the trip to Cuba twice to film on the hallowed grounds of the home Hemingway abandoned just as Fidel Castro came to power.

“It was exactly how he left it. His booze is in the bottles, his record is on the record player, his books are on the shelves, his trophies are on the floor,” related Burns.

Added Novick of her two Cuban trips to Finca Vigía: “If you go there as a tourist, you just get to peer in the windows, but it’s not the same as being inside. They used to let the public in on tours, but so many little objects” were stolen by patrons, she said.

In addition to interviewing contemporary authors about Hemingway’s substantial influence on English prose in the first half of the 20th century, Novick and Burns were able to convince Hemingway’s son Patrick, now 92, to sit for their cameras.

“He was incredibly gracious and open about his father and his father’s work and what mattered to him,” Novick said. “I explained to him that we were interested in an honest and fair…look at Hemingway the whole human being, and celebrating his great work in that context.

“We were interested in him because of the books he wrote, his literary output, his accomplishments on the page. He was a complicated artist who led a complicated life.”

Patrick Hemingway and other members of the family allowed the filmmakers access to many of Hemingway’s documents, letters and original manuscripts, many of which still bore his handwritten notes. They were also given permission to film Hemingway’s papers housed within the collection of the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library in Boston.

To make Hemingway come alive Burns and Novick engaged the services of actor Jeff Daniels to read excerpts of his prose and letters. That was in March of last year, and Daniels had already left New York for Michigan—as Burns described it, in “rehearsal” for the upcoming lockdown.

“We recorded Jeff Daniels on March 1 and 2 [2020]. We were doing it remotely from our studio,” said Burns. “I went home that night, and I have not left.”

Accordingly, he and Novick, who typically work in the same room, had to complete the edits, color correction, sound mix and other fine-tuning of “Hemingway” over Zoom.

“We had to get all the hi-res archival materials from archives that were locked and closed because of covid, so it was very dicey,” Novick said. “We had a couple of edit passes on our own, and then we got on Zoom to discuss what changes we wanted. And then we actually locked virtually.”

In addition to reviving Hemingway with the vocal services of Daniels, “Hemingway” includes one of the very last on-camera interviews ever given by the late Sen. John McCain. The Arizona Republican and Burns had been friends since Burns testified on Capitol Hill about the value of public broadcasting in the nineties. Burns had also entreated both McCain and then-Senator John Kerry (also a veteran of the Vietnam War) to assist on his Vietnam film, even though Burns said neither senator would be included in “The Vietnam War” given they were both prominent public figures at the time.

Burns was actually working on another film about the Mayo Clinic for which he entreated McCain’s participation. The senator, then but months away from dying, said he would also share his mind on Hemingway in the same interview—and also his thoughts on Muhammad Ali, the subject of Burns’s next documentary.

“I’d never had a threefer from a man who I adore as a friend,” Burns said, adding that there’s a moment when McCain spoke about the Mayo Clinic’s give-it-to-you-straight ethos in which the senator winked at the camera, as if tacitly acknowledging the seriousness of the brain cancer that would claim his life.

“I can’t look at it without crying,” Burns said of the footage of his late friend, who famously was imprisoned in a POW camp in Vietnam for six years. In fact, when “The Vietnam War” premiered at the Kennedy Center in Washington in 2017, Burns said McCain came up to him in the green room and embraced him in a bear hug.

“He said, ‘I love you Ken.’ I said, ‘I love you, senator,’” Burns said. “We’re the poorer for his absence.”

For all of his films, Burns works with the proviso that none of his benefactors are allowed any editorial input, nor are his subjects. Accordingly, he enjoys a degree of independence practically unheard of in filmmaking. He works at his own pace, and with the collaborators of his choosing. (His next film, about Ali, is co-directed by Sarah Burns and David McMahon, and will premiere on PBS in September. He and Novick will next collaborate, with Sarah Botstein, on a multi-part film about America’s “response” to the Holocaust, and another film about Lyndon B. Johnson.)

Because PBS shows his films, Burns says the broadcaster reserves the right not to air them, but “that hasn’t happened yet, knock on wood.”

And because his films are about America and its complex history, race, he said, is an inevitable factor, even when it seems ancillary (“The Vietnam War,” “The War,” “Baseball”) or when it’s baked in to the subject at hand (“Unforgivable Blackness: The Rise and Fall of Jack Johnson”).

“The interrelationship is mind-boggling. People like to say history repeats itself. It does not; it has never repeated,” Burns said of his films’ inevitable intertwining with racial issues. “Nothing has ever happened that was exactly the same. But as Mark Twain is supposed to have said, it rhymes.”

Even in “Hemingway,” we learn that the author used racial epithets time and again in his letters. Those words are blurred and bleeped when the film airs on PBS.

“It’s trying to be responsive to the power of language to hurt and to harm,” Burns said, adding that even previous films of his where the words were not blurred, such as in “Baseball” or “Jazz,” now came with a warning. “At the same time, we as filmmakers can’t pull any punches and pretend [Hemingway] wasn’t a guy who employed the N-word frequently,” Burns said.

In this way, Hemingway was as complicated as any of us, as tortured as any artist.

“The second you want to make a definitive statement about Ernest Hemingway, I’ve got a ‘yes but’ for you!” said Burns, adding that Hemingway and his work were “complicated and at times ugly and at times beautiful.”

As the subject of nearly all of Hemingway’s work was the inevitability of death, perhaps this was at least part of what led him to take his own life in Idaho, especially upon realizing he could never again return to his beloved Cuba following the disastrous Bay of Pigs invasion.

“Art sort of keeps the wolf from the door—the wolf being the trauma of our inevitable mortality,” Burns said. “This is the arc of a man’s life, and our film ends when [Hemingway’s] life ends.

“I think it was a special gift that he was willing to go up and stare into the abyss and still bring back extraordinary beautiful moments.”

“Hemingway” is now airing on PBS and is available on demand.

news via inbox

Nulla turp dis cursus. Integer liberos euismod pretium faucibua