The infamous human cost of war highlighted in Dror Moreh’s “THE CORRIDORS OF POWER” | INTERVIEW

The documentary filmmaker Dror Moreh doesn’t let his view of our species sneak up on you. Speaking on a video call from Tel Aviv recently, the director of “The Corridors of Power” minces no words.

“It’s a dark world,” he said, “and the human being is a horrible beast.”

Moreh would know. He’s spent the better part of the last decade making the documentary, which not only details the many, many instances of genocide within the last thirty years, but also the horrific moral calculus faced by world leaders who must determine what, if anything, to do about it. Bosnia. Rwanda. Libya. Kosovo. Sudan. And so many others, including Syria.

“I saw here in Israel these horrible pictures that came from Syria when [Bashar al-] Assad was butchering his people,” Moreh said. “Obama declared the red line [before] the chemical attack. Everyone was sure that America would respond and then didn’t respond.

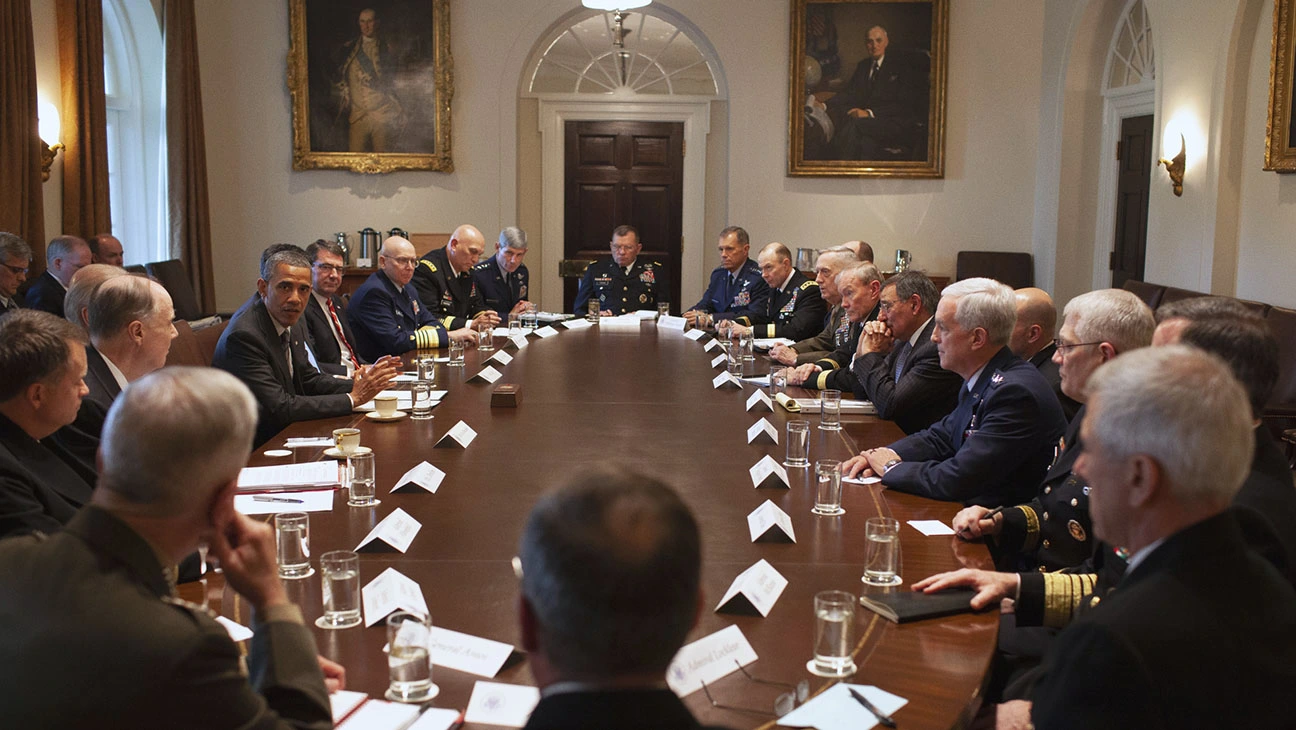

“I asked myself, what’s going on? What goes on in this room when you decide whether to do something or not.”

Moreh’s film features an incredible cast of decision-makers from administrations of both parties, such as Condoleezza Rice and Hillary Clinton, both former secretaries of state. His camera also captured some of the final interviews conducted with Colin Powell, Madeleine Albright and George Schultz.

But Moreh said he needed, if not a hero for his film, then a central figure who could walk us through the horrors of modern genocide. He found one in Samantha Power, the reporter-turned-diplomat whose book “A Problem From Hell” criticized U.S. foreign policy when it came to halting overseas systematic slaughter. Her book caught the attention of Barack Obama, who named her ambassador to the United Nations.

“Samantha for me was the movie in a way,” Moreh said because of her trajectory from reporting on genocide to eventually working as an ambassador. “Then understanding that the world says ‘never again,’ but this is happening and nobody is really” doing anything to halt such crimes against humanity, he said.

Having Power involved also unlocked the door to many other participants. Once one source trusted him, the gatekeepers were apt to allow him access to Washington’s power players. Thus, Moreh spoke to former members of the Clinton, Bush 43 and Obama administrations—as well as even some from as far back as Ronald Reagan, such as Schultz.

Moreh said that during his final interview with Power, he asked how she was able to sleep at night knowing that atrocities in Syria were going on but the Obama administration wouldn’t aggressively intervene militarily.

“I said to myself, as someone who believes in [the] responsibility [of] ‘never again,’ if Samantha Power is [already] in the room, then there is probably nothing to be done,” the director said glumly. “I believe if more people would be like Samantha Power, the world would be a much better place to live in.”

Among the most awful footage Moreh includes is of young soldiers in the former Yugoslavia executing Albanians and Bosnians as part of the ethnic cleanse that took place in the early-nineties. The soldiers carry out their duty seemingly without compunction, shooting their victims in the back while casually smoking cigarettes.

“Human beings are capable of doing horrible things,” said Moreh. “On one hand you see people who write symphonies or [create] movies. On the other hand, there are people who…”

He paused, as if trying to put into language the horror of those on-camera executions.

“I am lost for words sometimes. We’ve seen footage from Auschwitz and you see [that level of horror], but there is something [in the Yugoslavia footage] in the way that people are shooting almost like it’s their day job. I cannot really understand how you bring people to this. How do you make them dehumanize other people so much?”

Moreh admits he has more than a touch of PTSD from working on “The Corridors of Power.” What keeps him awake is the knowledge that so many of the people who were murdered in genocides perhaps hoped that someone would save them, although no one did. To wit, his film includes the tearful testimony of a U.S. diplomat recalling informing her local staff in Rwanda that the foreign service officers were being recalled, but they could not take along the locals, who would almost certainly be preyed upon by the Hutu machete squads.

Thus continues the ongoing discussion—-internally and internationally-—if the United States should take care of its own interests first, or if it is its destiny to be, as some believe, the global policeman for good. However, if the U.S. military, or that of other countries, can’t or won’t come to the aid of the oppressed, Moreh said, at least people can press their politicians to do something to help out the greater human family.

“Take for example Darfur, where the American public was really, really engaged and pushed the [George W.] Bush administration to do something about it. And they did,” he said of the ugliness in Sudan. “They didn’t intervene militarily, but they called it genocide while it was happening. They managed [to get in] huge amounts of support and food into Sudan.

“When people show that they care, when they push their representatives to act, then something happens. The last few years have proven to us that we are interconnected, that things that happen somewhere else in the world affect us.”

Moreh credits Showtime with allowing him the time and funding to fully flesh out “The Corridors of Power” as he hoped. Had he not locked picture earlier this year, it’s probable his film would likely also have touched upon the war in Ukraine.

“Because Russia decided that Ukraine is to ‘de-Nazify,’ whatever that [means], millions of people are now sitting in the dark, cold; they don’t have electricity, food is probably scarce,” Moreh said, adding that similar problems exist in both Ethiopia and other places, such as the ongoing pogrom in Syria against the Kurds.

Moreh, who is Israeli, lives in Berlin with his wife. Despite the seriousness of his film subject, he describes himself as a happy person overall, and that his aim with “The Corridors of Power” wasn’t to cast blame, but rather to understand what it was like to be in the room where decisions about the geopolitics of genocide are decided.

The United States, Moreh believes, can in fact be a global force for good. Through his research and filming, the filmmaker came to admire the American experiment all the more. This country has acted in the vested interests of others many times before, and can—perhaps should—do so again.

“At the end of the day for me, those people in the situation room in America are good people— each and every one of them,” he said. “We have to remember that the perpetrators are doing the bad things. The people in America have the power to stop them, but that power comes with consequences: American personnel are going to lose their life if there is military intervention somewhere.”

While he admits “The Corridors of Power” may not be an enjoyable movie to watch, Moreh expresses his hope that people will at least come to a better understanding of the structures of power that must tackle these seemingly impossible questions.

“I think if we do care about what goes on in the world, and we want a better world to live in, people need to understand that,” he said. “People need to understand that those lessons that we thought that we learned are easily forgotten—but ‘never again’ keeps [happening] over and over.”

“The Corridors of Power” is in select theaters

news via inbox

Nulla turp dis cursus. Integer liberos euismod pretium faucibua