INTERVIEW: “Ultimately, it’s the deepest quest of all,” Errol Morris speaks with us about his new film “My psychedelic love story,” it airs tonight

Even as we spoke on the phone last week, filmmaker Errol Morris said he was still putting the finishing touches on his new documentary, a version of which I had seen not long before the Oscar-winning director of “The Fog of War” and “Gates of Heaven” chatted with me from his home in Massachusetts.

Until recently, he was still color correcting and filling in the musical score. Letting go of the “final edit” is often the most difficult part of making a documentary, he said.

“It’s inevitable that you always imagine you could do things better if you had more time, or things you felt were more important but left out” of the finished product, Morris said. “But I’m pretty happy with this.”

The “this” Morris spoke of in such an amused, jovial tone was his new documentary, “My Psychedelic Love Story.” The version he screened for AFI FEST and DOC NYC wasn’t the finished product, he says, but whatever iteration he turns in to Showtime, “My Psychedelic Love Story” will premiere on the premium cable channel today.

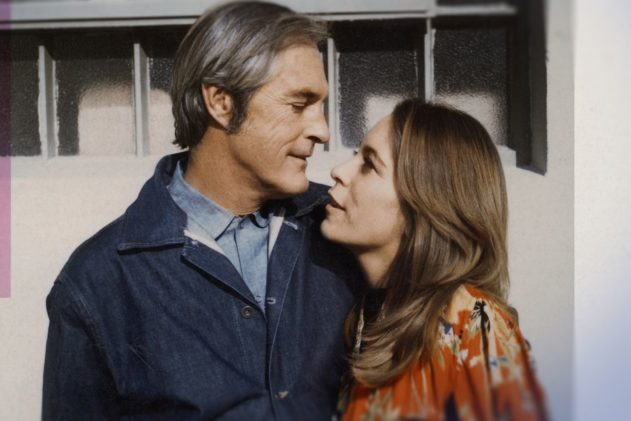

The documentary takes as its subject Joanna Harcourt-Smith, LSD guru Timothy Leary’s one-time lover. But as Leary was preaching the gospel of psychedelics, he informed on several others in a bid to stay out of jail. Via interviews with Harcourt-Smith, “My Psychedelic Love Story” not only recreates the Swingin’ Sixties but also asks its subject if she was on the government’s payroll, an innocent bystander or something else entirely.

As in his previous work, Morris made use of the “Interrotron” machine to prompt Harcourt-Smith to speak more freely on camera. This device serves to put the subject more at ease—and has often led Morris’s interviewees to admit to some shocking things on camera.

“With the Interrotron, [difficult] questions become an examination and investigation of personhood and of character,” Morris said. “Who this person is and, even more importantly, how they see themselves.”

Accordingly, Morris said his goal with “My Psychedelic Love Story” was not so much to shake down Harcourt-Smith for juicy soundbites, but rather to prompt her to examine herself—including the million-dollar question of whether or not she was in fact planted by the government to get close to Leary and his activities.

“To me that is the real power of this story,” Morris said. “And this was in the middle of a love story. If the question is did she really love Timothy Leary, I think the obvious answer is yes.”

Morris arrived on the scene in 1978 with “Gates of Heaven,” a documentary film about a California pet cemetery. From there, Morris has largely spent the next forty years asking hard questions of many figures who would probably rather not be introspective. These include Donald Rumsfeld in “The Unknown Known,” former defense secretary Robert McNamara in “The Fog of War” (for which Morris won the Oscar) and, also this year, Stephen K. Bannon in “American Dharma.”

Morris admits that his personal politics veer leftward, which naturally led me to inquire how he was able to get such prominent right-wing figures to agree to be interviewed.

“I suppose one answer is, I’m not sure. Another answer is, “I give them an opportunity to talk and to try to capture what they say,” Morris said, adding he believes his own track record of being trustworthy might also have something to do with it.

“Steve Bannon, for better or worse, admired me and my films,” Morris said of the man who himself produced movies long before joining the Trump administration. Morris said the two previously crossed paths at Telluride when he screened “The Fog of War” there, which Bannon watched beheld from the audience.

“The idea of using movies as a ‘way in’ to how a person sees the world and how they see themselves I think is very, very important,” Morris said. “It’s integral to my work and how I make movies.”

That goes for interviewing people he vehemently disagrees with, such as Bannon. Even though Morris finds Bannon’s views and beliefs “despicable,” he was shocked when some critics decried “American Dharma” as an “apologist” film about Bannon.

“The idea to me is utterly ridiculous,” Morris said of such criticism, adding that it was his goal merely to see the world through Bannon’s eyes. “It’s ultimately a story about a person who is inherently deceptive. There’s no constructive platform there. It’s a platform about tearing down policies, tearing down beliefs, [and] tearing down, in many ways, the entire idea of America.”

Likewise, Morris said the reception to “The Fog of War,” in which McNamara discusses frankly crafting the Kennedy and Johnson administrations’ failed policies in Southeast Asia, was too often framed as offering McNamara a redemptive arc. The filmmaker sees it otherwise.

“[Audiences] think somehow it’s McNamara seeing that he’s done wrong and trying to redeem himself. I don’t see the movie that way at all. I see a man who knows that he’s done wrong and sees no possibility of redemption,” Morris said. “At the time I described him as something like the Flying Dutchman: destined to sail the world forever hoping for redemption and never finding it.”

However, even though Morris was highly critical of McNamara’s decisions that escalated U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War, resulting in the loss of some 58,000 American warriors in that conflict, as well as perhaps uncountable numbers of Vietnamese civilians, Morris insists that he, even if begrudgingly, came to not only respect but in fact to love McNamara, who died in 2009.

“Do I see him as a war criminal? Yes, I do. Did I love the guy and respect him? I did,” Morris said in his amiable fashion. “This is the oddity.”

Even McNamara’s son, Craig, told the filmmaker that as his father neared death, he confided to the family how much he truly enjoyed being interviewed by Morris.

“His father told him, ‘I really like what Errol has done, but don’t tell him.’ He told me anyway,” Morris said with a chuckle.

If “The Fog of War” was an attempt by McNamara to perhaps come to terms with his sins, Morris believes Rumsfeld had no such desire when being interviewed for “The Unknown Known.” Rather, Morris thinks Rumsfeld continued to maintain a cynical self-justification for the Iraq War to the point of being a “bullshit artist,” which Morris says is a fair label for George W. Bush’s first defense secretary.

But with “My Psychedelic Love Story,” Morris believes that his new subject Harcourt-Smith is closer in introspective temperament to McNamara, and asked her such hard questions as whether she was used by the government or if she ever truly loved Timothy Leary.

SEE ALSO: Sam Weisberg’s 2011 article about “TABLOID”

Mostly, he hopes audiences will come along on Harcourt-Smith’s quest to figure out who she has been over the course of her intriguing life.

“Ultimately, it’s the deepest quest of all: to figure out who we are,” Morris said. “It’s not the kind of thing you can just write down on a pad of paper. Maybe it’s that exploration itself which is deeply moving and important.”

Morris of course has future projects planned, including an adaptation of John Le Carré’s autobiographical novel, “The Pigeon Tunnel.” About this, and the remainder of his future, he remains philosophical.

“There is only one true philosophical question: what to do next,” he said. “I have a whole number of projects in the works, and God willing, I hope to continue working!

“Years ago someone asked me, ‘Why do you make movies?’ And the simple answer is, so I can make more movies,” he said. “I suppose my ultimate hope is [audiences] want to see more of what I have to offer. What else am I going to do with myself?”

“My Psychedelic Love Story” premieres on Showtime today.

news via inbox

Nulla turp dis cursus. Integer liberos euismod pretium faucibua